Insights

Competition and Restrictive Practices Law Summer News

Sep 16, 2020Summary

Summer 2020 was characterized by two significant news items: one in the area of merger control and the other in the area of restrictive practices.

- On 28 August 2020, the French Competition Authority prohibited a merger for the first time since its creation. This transaction involved the takeover of a hypermarket in the Troyes agglomeration and the proposed remedies were not sufficient to address the competition concerns identified by the Authority.

- A little earlier, the French Supreme Court handed down an important ruling in the Expedia case, in which it confirmed that the action undertaken by the Minister of the Economy to punish practices restricting competition is of public order under French law (“loi de police”). It is therefore impossible to avoid it by means of a clause designating a foreign law.

Competition and Restrictive Practices Law Summer News

Summer 2020 was characterized by two significant developments in the area of merger control and restrictive practices. On 28 August 2020, the French Competition Authority (the "Authority"), for the first time since its creation, prohibited a merger operation involving the takeover of a hypermarket in the Troyes agglomeration. This prohibition is motivated by the inadequacy of the proposed remedies, which the Authority believed were not sufficient to address the competition concerns identified (1).

Earlier, the French Supreme Court (the "Supreme Court") handed down an important ruling in the case relating to the tariff parity clauses imposed by Expedia on its hotel partners. In this decision, whose scope could be extended to all restrictive competition practices, the Supreme Court confirmed that the action of the Minister of Economy (the "Minister") constitutes mandatory provisions of French law that are intended to apply even in case of a clause designating a foreign law. It is therefore difficult, if not impossible, to avoid it (2).

1. First prohibition of a merger by the French Competition Authority

On 7 June 2019, the Casino group announced in a press release the sale of several stores, including a hypermarket under the Géant Casino banner located in the Troyes agglomeration1. The company Soditroy, which also operates a hypermarket under the E. Leclerc brand in this agglomeration, and the Association of E. Leclerc distribution centers (of which all E. Leclerc store operators are members) intended to take joint control over this hypermarket, which would then be operated under the E. Leclerc banner.

With this in mind, the parties to the merger notified their project to the Authority during fall 2019, which, in light of certain competition concerns (which we will develop below), opened an in-depth examination phase (Phase II) on 24 October 2019.

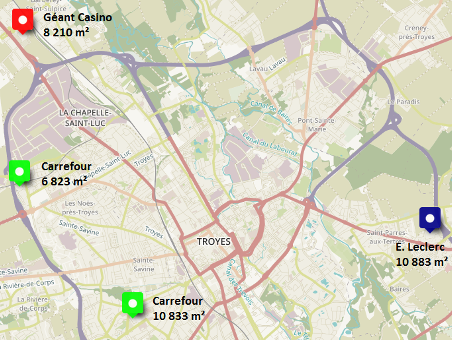

Indeed, as can be seen from the map below, the planned transaction would have led to a shift from 3 to 2 hypermarket groups in the Troyes agglomeration and to the creation of a duopoly between Carrefour and E. Leclerc.

Source: French Competition Authority

After conducting a market test among the different operators present in this geographical area (hypermarkets, supermarkets, discounters, national and local suppliers, etc.) and conducting surveys among the consumers concerned, the Authority more specifically identified:

- A risk of unilateral effects that would have resulted in price increases (or lesser price decreases) due to the disappearance of competition between the E.Leclerc hypermarket and Géant Casino hypermarket, all the more so as the Authority had observed a higher price positioning of the latter.

- A risk of coordinated effects between the Carrefour and Leclerc hypermarkets, which could have tacitly harmonized their behavior, all the more so as the retail distribution market for consumer goods is very transparent and the two brands would have had equivalent sales areas.

In order to obtain the Authority's authorization to carry out their project, the purchasers did attempt to offer behavioral commitments, consisting in particular of a reduction in the sales area of the Géant Casino hypermarket, but the Authority considered that these commitments did not remove the competition concerns identified and that they would also have led to a reduction of the offer available to consumers.

Finally, it was only on 28 August 2020, after nearly a year of examination, that the Authority considered that no satisfactory remedy was available and therefore prohibited the transaction. Although the decision has not yet been published, three observations can already be made:

- First of all, such a decision is unprecedented in France, since no merger had previously been formally prohibited by the Authority. Such prohibitions of mergers are not frequent at the European level, but over the last ten years, the Commission has nevertheless prohibited a dozen proposed mergers: between Ryanair and Aer Lingus, between HeidelbergCement, Scwhenk and Cemex, between Siemens and Alstom, between Tata Steel and ThyssenKrupp or between Telefonica UK and Hutchison 3G UK.

It is true that, in practice, when the notifying parties find that they are unable to propose remedies that would remove the Authority's competition concerns, they prefer to withdraw the notification. This is, for example, what happened earlier this summer in connection with a proposed merger in the oil pipeline sector2. While such an option has the merit of simplicity, it nevertheless closes the door to the publication of a decision, and thus to any appeal against the prohibition decision. In this case, it will be interesting to see whether the parties intend to challenge the Authority's analysis before the French Administrative Supreme Court (Conseil d’Etat).

Such an action led, in the Telefónica UK / Hutchison 3G UK case mentioned above, to the cancellation in May 2020 by the Tribunal of the European Union of the decision by which the European Commission had refused the proposed acquisition3.

- Secondly, it can be noted that the duration of the procedure was particularly long, even if the information published at this stage by the Authority does not make it possible to identify the cause. Is it due to the incompleteness of the notification file? The lengthy negotiations on potential corrective measures? The Covid-19 situation? In any event, after having opened Phase II on 24 October 2019, the Phase 2 period of 65 working days (which can nevertheless be suspended by the Authority through the "stop the clock" procedure in the event of incompleteness of the file) should have expired at the end of January 2020. It is very often the case that the time required to examine an operation is extremely long. This case is just an illustration. This time constraint must be perfectly integrated by companies planning an operation.

- Finally, on the merits, it will be interesting to examine, when the decision is published, the Authority's analysis of the competitive pressure exerted on the hypermarkets in question by other distribution channels (supermarkets, discounters, drives, etc.), which is not mentioned in the press release. Indeed, it would be a pity if an overly dogmatic vision of the definitions of the relevant markets ultimately led to the closure of an hypermarket rather than its transfer to another owner, a fortiori in this period of economic crisis.

2. Expedia case: a jurisdiction clause is not enough to bypass the control of the Minister of the Economy over restrictive competition practices

While the tourism sector is going through an unprecedented crisis due to the Covid-19 epidemic, hotels may find some small consolation in a decision dated 8 July 2020 of the French Civil Supreme Court (Cour de cassation, 8 July 2020, 17-31,536). Indeed, the latter has just confirmed most of the decision dated 21 June 2017 by which the Paris Court of Appeal had sentenced the Expedia group to a civil fine of 2 million euros for having introduced price parity clauses in its contracts with hotel owners. It therefore confirms that the Minister's control over price parity clauses, and probably over all practices restricting competition, is indeed a mandatory law (ordre public) from which it is not possible to escape by means of a jurisdiction clause.

As a reminder, in February 2011, following an investigation by the General Directorate for Competition Policy, Consumer Affairs and Fraud Control (DGCCRF), the Minister had summoned before the Commercial Court of Paris several companies of the Expedia group (which offers its customers to book online accommodation in hotels in France and abroad) on the basis of the former Article L. 442-6, III of the French Commercial Code (which allows the Minister to act against restrictive practices of competition) for the annulment of price parity clauses and "last room available" clauses present in several contracts concluded between Expedia and the hotels referenced on the platform.

More specifically, the parity clause provided that the hotel had to automatically make Expedia benefit from conditions at least as favorable as those granted to other distribution networks (competing platforms, sales by the hotel on its own website, direct sales, etc.), so that the companies of the Expedia group benefited not only from the lowest rate charged by the hotel, but also from any additional advantage (free breakfast, etc.). In addition, in application of the "last available room" clause, regardless of the number of rooms available for sale, the hotel owner was required to offer Expedia its last available room.

Prior to any defense on the merits, Expedia had then argued that the Minister's action was inadmissible in two respects, since the contracts concluded with the hotels:

- contained a jurisdiction clause designating the English courts; and

- designated English law as the law applicable to any dispute.

The Paris Court of Appeal (CA Paris, June 21, 2017, No. 15/18784) did not welcome these arguments, and had considered:

- that the action attributed to the Minister was within the jurisdiction of the national courts and that the clause attributing jurisdiction to the British courts was unenforceable against the Minister; and

- that the Minister's action was a tort action so that a clause designating a foreign law could not be set up against the Minister, as a third party to the contract.

The Expedia group then formed an appeal before the Cour de cassation. In a decision dated 8 July 2020, the French Supreme Court thus essentially confirmed the appeal decision.

Firstly, with respect to the merits of the case and the assessment of the disputed clauses, the French Supreme Court approved the appeal decision after having recalled that article L. 442-6, I, d) of the French Commercial Code provides that clauses or contracts providing for the possibility of automatically benefiting from more favorable conditions granted to competing companies by the contracting party are null and void. However, the French Supreme Court censured the reading made by the Court of Appeal of the clauses relating to the last available room, which only require hotels to allow the reservation of the last available room through the Expedia website under the conditions provided for other channels, but do not require that the last room be actually sold through Expedia’s website. This clause was therefore not significantly imbalanced. But it is not the most important contribution of the judgment.

Indeed, with regard to the procedural arguments relating to the applicable law, the French Supreme Court notes that the regime relating to torts is characterized by the intervention of the Minister for the defense of public order. For the supreme judges, the means of action available to the Minister, in particular to seek the pronouncement of civil penalties, precisely illustrate the importance that the public authorities attach to these provisions. Thus, articles L. 442-6, I, 2 and II, d) of the French Commercial Code in their version applicable at the date of the dispute contain mandatory provisions whose application is binding on the judge who must rule on the dispute, without the need to seek the conflict of laws rule leading to the determination of the applicable law.

It is true that the Decree no. 2019-359 dated 24 April 2019 amended the title of the French Commercial Code relating to restrictive practices, so that articles L. 442-6, I, 2 and II, d) of the French Commercial Code applicable to the dispute in question no longer exist as such. However, under the terms of the new article L. 442-4 of the French Commercial Code, the Minister now has jurisdiction over the practices covered by articles L. 442-1 (abrupt termination, significant imbalance and advantages without consideration), L. 442-2 (resale outside the network), L. 442-3 (retroactive discounts), L. 442-7 (abusively low prices in the food sector) and L. 442-8 (reverse auctions) of the same Code. Thus, the scope of the decision of the French Supreme Court is not reduced, since it can legitimately be expected that this reasoning will in the future be transposable to all the above-mentioned restrictive practices against which the Minister may act.

Thus, foreign economic operators entering into contracts providing for the applicability of foreign law must be cautious, since the mandatory nature of the above-mentioned provisions may be invoked by their co-contractor during a litigation initiated in France.

1. Press release of Casino group, 7 June 2019.

2. Authority’s Press release: « Oléoducs : l’Autorité prend acte du retrait de l’opération de prise de contrôle exclusif de Trapil par Pisto », 24 July 2020.

3. General Court of the European Union’s press release, 28 May 2020.

Related Capabilities

-

Antitrust & Competition

-

Business & Commercial Disputes