Insights

PDP Financing in Aviation

Jun 15, 2020The global aviation industry is experiencing a downturn of unprecedented proportions. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has forced governments around the world to close their countries’ borders and ban commercial flights over the last few months. Those airlines that are now beginning to operate again will do so on the basis of a reduced capacity, and may not return to full capacity for some time. In today’s locked down world, businesses in all industries will be looking at a change in priorities: from growth to continuity; from investment to cash retention.

Amid the pressure of reduced revenues and daunting financial forecasts, airlines and leasing companies are concerned to shore up their capital reserves and manufacturers will be looking to ensure that revenues remain constant while they undergo the costly work of manufacturing aircraft. With these two particular issues in mind, this article will hopefully serve as a timely reminder of (or introduction to, as the case may be) the subject of pre-delivery payments (“PDPs”), in the context of the manufacturing of aircraft, and the related financing arrangements for PDPs.

Manufacturers typically receive pre-orders for aircraft from airlines, for delivery at a later date. They incur significant costs during the manufacturing process and so the purchaser will usually be required to make periodic PDPs to the manufacturer during that process, to offset some of those costs. PDPs constitute part payment of the full purchase price of the aircraft, with the balance of the purchase price (that is, the full purchase price less all paid PDPs) becoming due on delivery of the completed aircraft.

PDPs can represent as much as 30% of the gross purchase price an airline pays for its aircraft, excluding discounts, so airlines often turn to the finance markets to procure financing for PDPs. This allows them to use their own cash reserves for other purposes, rather than using that cash to service PDPs for aircraft which will not be operational, or earning revenue, for months or even years to come.

How PDP financing works

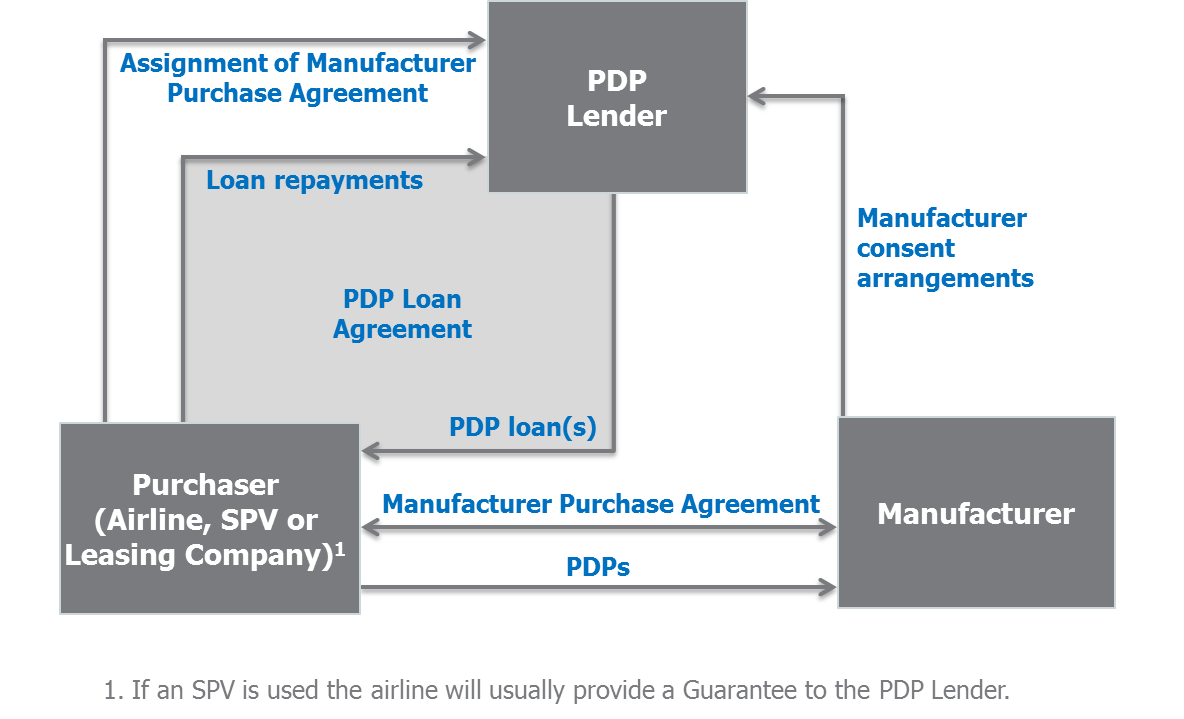

A typical aircraft PDP financing structure can be summarised as follows:

- The purchaser of an aircraft (which can be an airline, a leasing company or, for reasons discussed below, a bankruptcy remote special purpose vehicle) borrows money under a loan facility for the purpose of funding all or part of the PDP amounts payable to the manufacturer. PDPs are usually paid incrementally to reflect periodic progress payments payable upon the achievement of certain milestones in the manufacturing process of aircraft. Consequently, loan drawdowns under a PDP loan are also incremental.

- The purchaser pays interest on the PDP loan throughout its term.

- There are no principal repayments during the term of the PDP loan; full principal repayment is made upon delivery of the aircraft, at the end of the PDP loan term.

- The PDP lender obtains a security assignment of the purchaser’s rights to purchase the aircraft, under the manufacturer purchase agreement.

- In a default scenario, the PDP lender can assume the position of purchaser of the aircraft, as against the manufacturer, in one of two ways:

- the PDP lender can “step in” to the manufacturer purchaser agreement, to the extent it relates to the relevant aircraft, and assume the purchaser’s rights to purchase the aircraft under that manufacturer purchase agreement. The PDP lender will become subject to certain obligations under the purchase agreement, with regards to its purchase of the relevant aircraft; or

- if the PDP lender, or its affiliate, has an existing purchase agreement in place with the manufacturer, the parties could agree that the relevant aircraft under the PDP financing becomes subject to that existing purchase agreement, enabling the PDP lender to benefit from the terms and any credits which it (or its affiliate) has already agreed with the manufacturer separately. In such a case, the provisions of the purchaser’s purchase agreement which relate to the relevant aircraft are terminated and the aircraft instead becomes the subject of the PDP lender’s (or its affiliate’s) purchase agreement.

6. Where a relevant default has occurred, the manufacturer has a prevailing right to terminate the purchaser’s rights under the purchase agreement to prevent the PDP lender from exercising its “step in” rights (as described above), in certain circumstances. If the manufacturer exercises such an option then it is required to repay to the PDP lender the PDP loan amounts drawn down by the purchaser and paid to the manufacturer.

How PDP financing differs from traditional asset financing

PDP financing is distinct from traditional asset-backed long term financing in a number of ways, including (but not limited to):

- PDP loans have shorter terms and the amounts borrowed are lower than amounts borrowed under longer term loans which are utilised to finance the majority of the aircraft purchase price.

- Periodic principal repayments are not made through the term of PDP loans. The full outstanding principal amount is instead repaid at the end of the PDP loan term.

- PDP loans are usually full recourse financing arrangements by the purchaser which are secured by a collateral assignment of the manufacturer purchase agreement.

- As described in more depth below, it is not possible for a PDP lender to obtain security over the aircraft itself (since it does not yet exist in completed form) or benefit from aviation insurance protection. Instead, PDP lenders are granted security over the purchaser’s rights to purchase the aircraft at delivery.

Advantages of PDP financing

The PDP model offers a number of potential advantages over traditional asset-backed financing:

- Margins on PDP financings are often higher than those for traditional longer term aircraft financings.

- In an enforcement scenario, where a PDP lender “steps in” and purchases the relevant aircraft, it will have the benefit of a brand new aircraft, potentially making it easier to remarket as compared with an older model. A PDP lender will of course be required to pay the remaining balance of the aircraft purchase price in order to take title to the relevant aircraft.

- The PDP lender stepping into the original purchaser’s purchase agreement will benefit from the discounted purchase price which airlines are often able to negotiate with a manufacturer.

- If the PDP lender is able to negotiate that the relevant aircraft will become subject to its own separate manufacturer purchase agreement (as opposed to the purchaser’s purchase agreement), when enforcing its “step in” rights, then the PDP lender could potentially benefit from any preferential terms or purchase price credits which it has already negotiated with the manufacturer separately, if those terms are more favourable than the equivalent terms which would otherwise be available to it under the purchaser’s purchase agreement.

- PDP lenders for an aircraft are often the first in line to finance the eventual purchase of that aircraft on delivery, so it can serve as a business development opportunity when it comes to long term financings of new aircraft.

Points to note in PDP financing

These are some of the issues which we advise our clients on when looking at PDP financings:

- Claw-back risk arises in PDP financings in the event that the purchaser becomes insolvent. In that situation, and depending on the extent of an insolvency officer’s powers in the relevant purchaser’s jurisdiction, the manufacturer may be forced to return the PDPs to the purchaser’s insolvent estate (that is, such amounts are “clawed back”). If such amounts are “clawed back”, then it follows that part of the purchase price monies will have been unpaid, because the manufacturer will no longer be in receipt of some or all of the PDP amounts. Who takes that so called “claw-back risk” is often the subject of much negotiation between the manufacturer and the PDP lenders. This risk can be mitigated by using a bankruptcy remote vehicle as the borrower under the PDP financing and the purchaser under the manufacturer purchase agreement, in which case the relevant airline will usually provide a guarantee to the PDP lender covering that vehicle’s obligations under the financing.

- The purchaser, manufacturer and PDP lender will look to negotiate their set-off rights. Each party will want the right to reduce its payment obligations by netting off any amounts it is owed, and a PDP lender assuming the position of a purchaser will often want to benefit from the purchaser’s set-off rights under the purchase agreement.

- The perception of PDP financing as closer to corporate financing than asset-backed financing is to some degree a fair characterisation, given that the PDP lender’s security comes in the form of an assigned purchase agreement rather than a security interest over the actual aircraft. A PDP lender looking to enforce its “step in” rights will need to pay the outstanding aircraft purchase price, as opposed to traditional asset-backed financing in which a financier has a right to take possession of the aircraft under its mortgage without making substantial payments up front.

Conclusion

In the current climate, with airlines’ passenger revenue down as much 90%, we may see an increase in the popularity of PDP financing, as airlines look to free up cash, financiers look for alternative investment opportunities and manufacturers look to encourage wider market participation in the financing of PDPs, which offer manufacturers a valuable source of income prior to completion of the manufacturing of aircraft.

Related Capabilities

-

Finance

-

Aviation Finance

-

Transport & Asset Finance